I can’t speak for anywhere else in the world, but this year’s Paralympics are inspiring so many people in UK right now.

Watch long enough and you start to completely lose sight of the disability and see instead an array of talented athletes performing at the pinnacle of their game. Team GB are rocking so many gold medals they’ll be able to balance the load at the other end of the bus at the end of the Italian Job by the closing ceremony.

One thing that I’m rapidly learning, helped by Oscar Pistorius’ outburst on Monday night, is that I still have a lot to learn about losing.

The Gulf

It’s hard to imagine an event other than the Olympics where the gulf in winning or losing is so great: thousandths of a second can mean the difference between gold and silver, or gold and no medal at all. Four years of one’s life dedicated to the pursuit of a solitary goal, four years of forsaking all the things that the rest of us take for granted like nights out with friends or Sunday lie-ins, four years of total absorption can come down to the time in between ticks of the second hand on a clock.

In one instant, all your dreams can be shattered.

Where else in sport can you see hopes raised so high, for so long, with such commitment, dashed within the literal blink of an eye?

Contrasting attitudes

I was sitting watching some of the swimming with K last night and we entered into a discussion on the relative reactions of the athletes to winning and losing medals. It seems to me there are 4 distinct types of events in the Olympics and Paralympics that all bring out varying reactions.

Team or match-based sports

Sports like Football, volleyball, (table) tennis and their ilk seem to encourage the biggest reactions in the competitors, which is understandable. Everything can rest on a single bout, a single fixture, where winning or losing can be the difference between medal and no medal.

The very nature of these kind of battles, coupled with the fact that they are the type of sports we are most used to seeing week-in, week-out, leads to the heightening of emotions, the outbursts of feelings beyond the control of the participants. Just witness Andy Murray’s 2 reactions in the Olympics after his individual gold and his doubles silver.

Individual “race” sports

In other words anything track-based, be it cycling, running or wheeling. The shorter the distance, the more profound the emotions: witness the elation of the sprinters against the amazement of the long-distance runners.

What they all have in common, though, is the sheer level of joy for the winner and the degree of circumspection for the “loser” – the other finalists who don’t quite get there. The response to missing gold tends to me a little more subdued than the team sports because most of the time the athletes have run as hard as they physically can and, because of that, they know they simply weren’t the best person on the day.

The old adage “may the best man win” holds very true and track athletes seem to be able to cope with only the slightest of frustrations.

Individual “turn-based” sports

Long jump, javelin or any other kind of throwing, jumping or field sports in general come with a much greater degree of placidity than most of the other events.

Because they get a series of attempts, the competitors who miss out on golds tend to know their fate ahead of time, so it’s not such a sudden or crushing blow.

Sure, they are disappointed when they don’t hit their targets, or if they get usurped on the leaderboard by the final throw of the day, but it never seems like too big a deal to them and they are always ready to congratulate the winner.

Swimmers

Watching the Paralympians on Monday night, I realised that swimmers seem to be a totally different breed of athlete compared to almost everyone else competing at the Olympics or Paralympics.

I have literally never seen an occasion when a losing swimmer has looked anything other than delighted for the winner(s).

I’m not so blinkered as to assume it never happens, but in every instance of swimming I’ve watched, this summer or seen in the past, the winners are always over the moon and the other medallists and finalists always seem genuinely happy for them.

Oscar

Of course, talking about losing and coping with it, the immensely talented Oscar Pistorius damaged his own brand and reputation on Monday night after claiming that Alan Oliveira had essentially cheated his way to gold by using longer-than-permitted blades in the T44 200m final.

What was shocking about Oscar’s pronouncement, however, was not the issue he had with his rival’s blades – something that’s been rumbling for months, by all accounts – but the timing of his decision to complain in the media line-up immediately after the race had finished.

We can all recognise that rush of emotions you feel when you’ve been hard done by, but whether or not Oscar has a point and the regulations need to be re-examined, it was childish, unprofessional and very poor form to attack the gold medallist in that place, at that time, in that manner.

Of course, Oscar apologised and recognised his mistake, but his error teaches us all what we need to remember about not finishing first.

It’s down to us alone

When we fail to achieve something we set out to do, it’s only right that we feel a pile of negative emotions.

When we fail an individual challenge, it’s natural that we’re angry or disappointed with ourselves.

When we fail against someone – something we all recognise as “losing” – it’s so much easier to deflect that anger and disappointment away from ourselves.

Some people blame the winner – cheating, better opportunities, more experience – while others blame outside influences – the wind, the track, the lane-choice, extra funding.

What we rarely stop to look at is that, more than anything, we’re still just annoyed with ourselves, because it’s still down to us.

The reason the person who finishes 8th in the 100m final doesn’t look as devastated as the person who finishes 4th is because they know before the start of the race that the likelihood of them winning is slim.

They don’t build up their expectations and they understand that they are not performing to the standards of a gold medallist. Finishing 4th means you were so, so close to getting on that podium and you feel all those associated emotions because you feel like maybe, just maybe, had everything been right, you could have found that 5 thousandths of a second to get you over the line first.

Accepting yourself

We can only truly learn to become magnanimous losers when we understand what it takes to win.

If we know we haven’t put in the work, or if we know we can’t make the grade in a certain way, then we understand that we have lost to a better person.

If we can’t see that someone else has worked harder, longer or more diligently than we have, we find it hard to accept our loss.

But rather than being cynical and wondering what they have done to give themselves an advantage over us – longer blades, illegal substances, whatever else we can imagine in our wound-up, emotional state – we should turn inward and wonder what more we could have done to get ourselves over that line first.

If you want to win, focus on yourself and your work rather than your opponents and theirs.

To be better, stronger or faster, you’ve got to be more dedicated, more focused and more passionate. Only then can you achieve the victory to which you aspire.

Until then, learn to lose with grace.

*****

When did you last lose out on something you were truly passionate about or prepared for? How did you deal with it, or how would you deal with it differently?

Have you been inspired by the Paralympics (or its cousin)? What are you doing off the back of the people who have spurred you on?

Post credits:

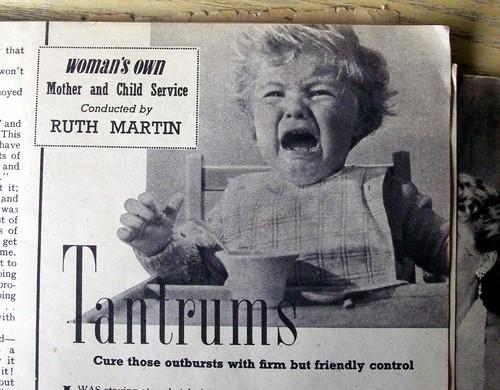

Blanket Tantrum from themanikone

Tantrums by the justified sinner